A Redondo Beach Couple Experiences Kumbh Mela—a Spiritual Pilgrimage of 150 Million in India

Behind their leap of faith.

- CategoryUncategorized

- Written by Alison Clay-Duboff | Photographed by Ken DuboffAlison Clay-Duboff

- Photographed byKen Duboff

People asked us, “What is this Kumbh Mela you are going to?” Then the same people asked, “Why? Why go there?” There was and is only one answer. My husband is crazy.

How to describe this unthinkable, absolutely unimaginable event is a task where forging emotions into words is as elusive as the blind devotional faith that is Kumbh Mela. But first a little personal history.

Some 20 years ago while living in Saudi Arabia, I developed a deep, sibling-like bond with an Indian employee—a bond irrespective of culture, religion, socioeconomic ranking and geography. After three years in Riyadh, the time came to say goodbye to my “Indian brother.” I didn’t know if I’d ever see him again, and it broke my heart.

The years of my life flowed past with a rhythmic symbolism akin to the Ganges, and this passage of time forged a clarity—an understanding of what’s truly important. Emotional priorities rose to the surface, and floating atop the river of my life’s arc was a deeply earnest wish. I yearned to cast my eyes upon the sweet face of my Indian brother, Abdul … to communicate again with those eyes that before never required words.

Ken, my husband of 16 vibrant years, made it happen. In December 2017 Ken took me to India for a poignant and joyful reunion with Abdul and his family. There were so many beautiful moments, laughter and tears of yet another farewell, but there were also untold aftereffects. This trip to visit Abdul was only the beginning of our relationship with India.

Going to India was scratched off the bucket list. We could never recreate the magic of our time with Abdul and the three weeks spent visiting the major beloved tourist spots that India is famous for. It was a self-sufficient, living memory that would sustain me for the rest of my days.

Surprisingly, one year later we were flying off to New Delhi. We were making the long trek back to India—not to visit Abdul, but this time to take part in the world’s largest gathering of humanity on the planet.

Kumbh Mela is a Hindu festival that captured Ken’s attention. It attracts numbers of devotees and pilgrims so staggering and unimaginable that all you can do is go with the proverbial flow. There is only one trajectory: You have to let go, give in, surrender and trade in your individualism and your personal space to be one with 50 million souls.

The dates of the Kumbh are calculated in accordance to a combination of Zodiac positions of the sun, the moon and Jupiter. It occurs every 12 years. Ken told me he

really wanted to go, but I brushed it off. It would pass, this fascination. But it didn’t.

And when he told me it was his “10/10,” I told him to book it. That’s an act of true love!

After a year of planning and trade-offs (our side trip to Vietnam and Japan was my idea), we found ourselves back in Delhi. Our suitcases were laden with a myriad of items: photography gizmos, medications and sanitizers. There were chocolate kisses for the kids and potato chips to sustain us during the unchartered culinary experience of vegetarian tent glamping during our time at Kumbh.

Most of the 150 million pilgrims who come to Kumbh Mela over the course of 55 days to dip in the Ganges and cleanse themselves of their sins have painfully limited financial resources, so they sleep in the open air, having walked for days with firewood on their heads and children at their heels.

For Ken and me, sleeping in the open air was not an option; we required a tent equipped with basic necessities—private toilet and shower—and that’s what we got. What we didn’t get (our fault we didn’t ask) was a tent with heat (it was very cold at night) or the promised hot water for bathing.

But our “deluxe tent” came with electric blankets and electric teakettle. We brought a bottle of Scotch just in case, and it came in handy; we were both unknowingly carriers of a nasty respiratory infection.

Kumbh Mela was held over 55 days: January 15 through March 4. February 4 was the most auspicious bathing day; we planned our trip around this most sacred day, along with 50 million pilgrims.

This bathing takes place in the city of Prayagraj at the confluence of three rivers: the Ganges, the Yamuna and the “mystical” Saraswati. It is estimated that 150 million pilgrims visited during the course of the festival—some for a day and others for all 55 days.

Hindus believe that people who bathe in the sacred waters during Kumbh Mela are infinitely blessed as their sins are washed away and they achieve a closer proximity to salvation/enlightenment or “moksha.” The Kumbh’s temporary city is approximate 25 square miles and is constructed during 90 days before the opening ceremony. It is torn down at the conclusion of the festival within 90 days, as the waters again return to the riverbeds.

The 2019 Kumbh budget was estimated at US$400 million. It included car parking for 500,000 vehicles, 186 miles of roads constructed, 30,000 police and military personnel, 11 hospitals, 120,000 toilets, 22,000 sanitation workers, 22 pontoon bridges and 40,000 LED lights. Put it all together, and it’s by far the largest temporary city in the world.

Day 1

As the plane climbed up through the polluted sky, we watched Delhi disappear. After a spicy vegetarian airplane meal and a very rough touchdown, we once again welcomed Varanasi. Our same driver from the year before greeted us warmly and collected our bags. We were on our way!

A year in the planning would come to fruition after a scant 60-kilometer drive to Prayagraj. The only problem was that this 90-minute drive took almost eight hours due to an estimated 150 million people en route.

People travel to Kumbh by train, car, foot, camel and elephant. We chose a minivan with AC. Hour after hour, identical Indian villages crawled by my window in slow motion—each of them grey, bleak and crumbling but

accentuated with colorful fruit markets, brilliantly colored saris, cheap toys hanging from buildings and very happy holy cows.

And then suddenly, appearing out of nowhere, distant lights came into view and lit bridges glistened in the fog. It was a thrill unparalleled. We crossed bridges, our eyes wide. We were actually there. It was surreal.

People were on the move, walking in all directions. It was solemn—very quiet yet vibrant. It was odd how everyone was going in different directions. This was unexpected, but we didn’t have any intimation of what a temporary city should look like.

Arriving at our tent village was a small tour de force because we were lost and our driver was lost and couldn’t find our location. After multiple stops, asking for directions, we were wearily waiting to join our friends.

Molly, JB and Sandy flew in from their homes in San Francisco. Raju is our dear friend and owner of Incredible Real India tours. We first met him during our previous

trip to India the year before, as he had customized a private tour of his country for us. Along with Raju was his sidekick Dev.

It was late, and the line of tents was magically aglow. The sounds of people zipping up for the night sounded like cicadas.

Day 2

Breakfast was served in the communal dining room with fellow adventurers from all over the world. There were curry dishes and few Western options. We ate quickly and set off to explore.

Our collective adrenaline was abuzz. Ken and I had clocked hours of Netflix documentaries on this fascinating festival. I had a Kumbh Mela app on my phone. We were prepared, and we couldn’t wait to see the infamous Naga Sadhus (the naked wise men). It was time to meet them in the flesh, no pun intended. They wear no clothing, just ash, and some don a type of loincloth.

The Naga Sadhus have their encampments across the rivers, and due to the crushing amount of humanity trying to get access, the authorities closed the pontoon bridges. We were unable to talk our way across. We tried various pontoon bridges with the same results. Flashing our prestigious press passes was fruitless.

Resigned to staying put, there was much to see on our side of the banks of Mother Ganges. We walked along the dirt roads, paused for photos and selfies with passing pilgrims, admired saris drying in the light wind, observed pilgrims in their private moments of prayer. At the Ganges, multitudes of women adorned in colorful saris—as well as men stripped to their undergarments and splashing children—connected to their own personal reverence.

We took endless photos and spoke with those whose language matched ours … and many whose didn’t. A hand over a heart is universally understood. The sun had warmed, our spirits were high … and, as it turned out, so was my mounting fever.

By lunchtime I was dusty and exhausted. My cough racked my frame. We headed back to our tent village. We were all more or less ready for a pause.

Back at camp we had lunch: more curry and unknown dishes. I thought it was tasty—Ken not so much. The camp staff was most accommodating. They just couldn’t get Ken a non-veg meal. It was our little Indian home away from home. I even ran into a couple from Hermosa Beach, believe it or not.

Ken, our friend Raju and the gals from San Francisco wanted to go out again and find a bridge to the festival, so they left at about 4 p.m. Ken soldiered forth on an empty stomach. No curry had passed his lips; he had enough curry for a lifetime the previous year. JB hung back, and I retreated to bed—blanket burning, coat on, cell phone in hand to geotrack our group, which was lovingly self-named Cool and the Ganga.

Noises permeated my frigid canvas tent. I napped fitfully to the tunes of neighbors coughing; the incessant, live, singsong prayers; and lost-and-found alerts that rang out over 25 miles of very loud speakers.

But then fear set in—a subtle, subcutaneous panic. Why no communication? The geotracking wasn’t working. I had no idea where my people were or how they were. Were they trampled? Separated from each other and lost, not speaking the language? (No one ever knew where anything was. Directions were as illusive as personal space.)

Hours passed. I drifted in and out of sleep, cell phone glued to my hand. Ken was sick too—tired and under-nourished. I was on edge. I was alone and sick in a faraway land, in a semi-luxurious tent, with worry as my only companion.

Finally a group WhatsApp notification appeared in the now-darkened tent. The gang was together, they were experiencing amazing things, but they were lost and needed to find a boat to cross Mother Ganga back to our tents. Ken was fine. I was relieved but far from relaxed. I now knew it would be hours before their return.

Every now and then their locations would be revealed; at one point they were finally in the middle of the river, moving slowly. Then as suddenly as their coordinates appeared, there would be no more movement.

I was coming to terms with an undeniable reality. I physically could not make the next day’s journey to the main events: the procession of gurus being led by the sword-wielding Naga Sahus, which Ken and I had studied ad nauseam for more than a year.

Our friends eventually arrived back at camp around midnight. The kitchen stayed open for them, and dinner was consumed. After a fitful 90-minute nap, they left again at 2 a.m. to witness the holiest of bathing days with 50 million pilgrims and 200,000 naked warriors.

Ken kissed me goodbye. I held him tightly and wished him an amazing, once-in-a-lifetime experience. I couldn’t believe I wouldn’t be a part of his 10/10. It broke my heart.

As I laid in the dark of the tent, I chose to be grateful—knowing that Raju, Dev, Ken, JB, Molly and Sandy would give me Technicolor-rich descriptions of what they saw, experienced, felt. It would be as if I was there with them, I was sure of it, and that fact alone allowed me to accept my fate.

Day 3

I awoke to the sounds of military helicopters and more prayers—this time one in English. “Hallo hallo” rang out literally for hours. Communication via WhatsApp had been spotty at best through the night.

Not wanting to detract from their individual and collective experiences, I gave the gift of space. I put the phone away and refused the temptation to be a needy, worrisome wife.

As the hours crawled by I wondered when I’d see the gang again. Eight hours passed, 10 hours and finally word: They were at last on their way back.

I knew Ken’s only wish upon his return would be a hot shower to wash off the sweat, dirt, incense and campfire smoke. I also knew that wasn’t going to happen, so I spent two hours heating water in the little kettle, pouring it into the “sluicing bucket,” mixing it with bubble bath and covering the bucket with a towel to keep the heat in and the water warm.

I must have filled 100 kettles full of water. It was not an easy setup. I had to fill the kettle with cold water from the bathroom sink, which had to be unzipped and zipped up each time. (There were mosquitos in there, and Ken didn’t take his malaria medicine, as he had an allergic reaction back home.) Then I would heat, drain and repeat.

The geotracking was suddenly showing me that the group had advanced rapidly and was a few minutes’ walk away. I perked myself up and ran out, but not before adorning the entrance of the inside of the village with welcome signs for Cool and the Ganga. They all deserved a royal welcome. They had conquered the masses, accomplished a dream.

Stepping into the open world of the Kumbh’s greater area outside our camp village for the first time in two days, I was greeted by smiling ladies who wanted nothing more than to take a selfie with the American lady, which of course I obliged with huge smiles.

In the dusty, smoky distance, I could see Molly striding purposefully toward me (no sign of Ken). I recorded her arrival, gave her a high-five for her accomplishment and then spotted Sandy and Dev in the foreground. More video, more congratulations, but where was Ken?

It seemed like an eternity, but he arrived—having hopped onto the back of a passing scooter for the last leg of the trip back to camp. I hugged him as tightly as the very first time I hugged him some 18 years prior.

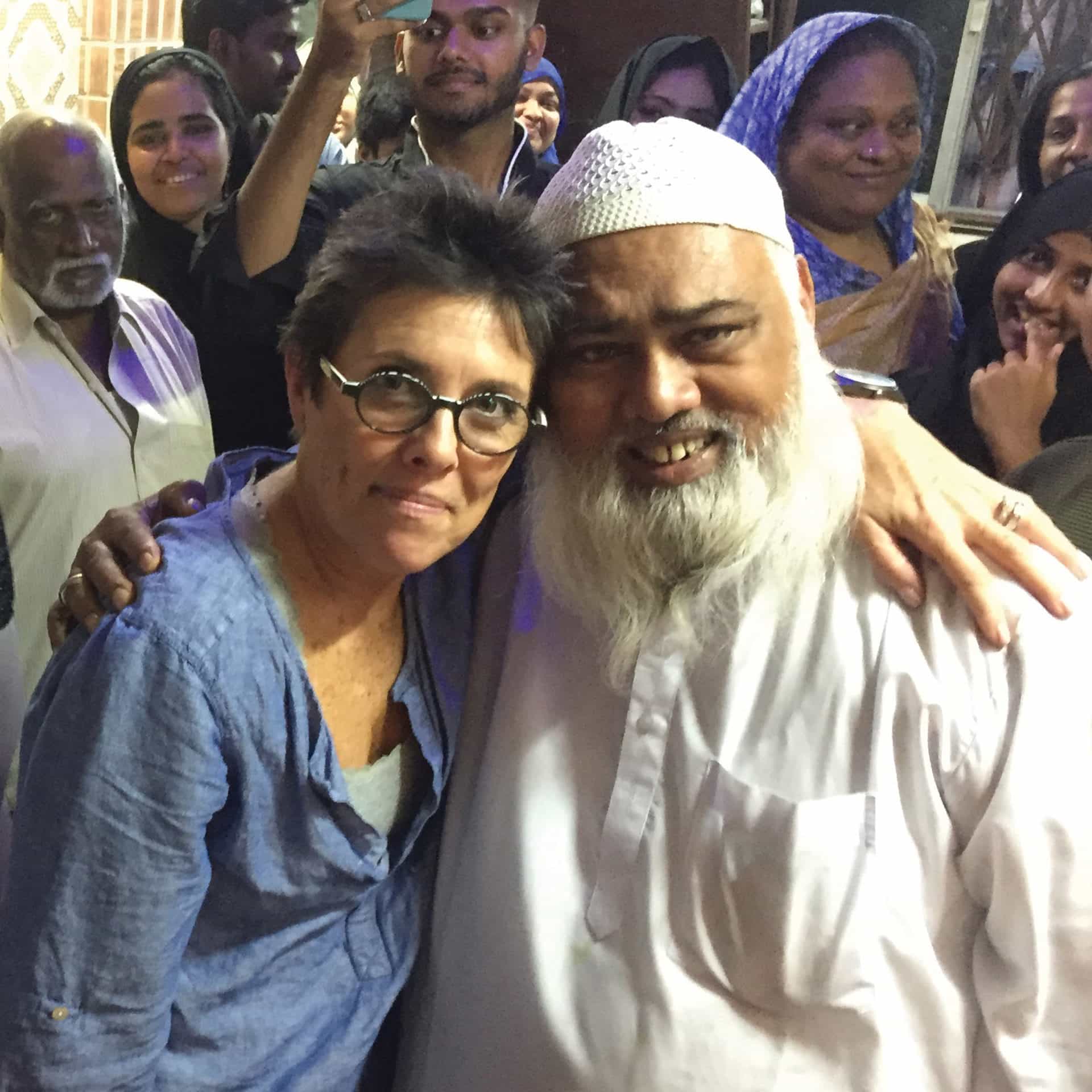

Alison reunited with friend Abdul and his family.

My six weary explorers and I came together for lunch. I tried to quell my curious enthusiasm, but persistently I besieged them like a little kid. I ached for the Techni-color, blow-by-blow reportage. They chatted amongst themselves, and I was clearly the outsider.

They laughed, and they relaxed and ate, which they had not done for several days. They shared private stories to which I was not privy. I retreated slightly into a respectful quiet until my questions refused to sit still inside me. Exhaustedly, sparingly, they parsed out details.

They talked about the crowds, being sardined together, the claustrophobic fear rising, how they clung to one another partially by design and partially against their will. They described the smoke from the cooking and warming fires, how the incense was suffocating. They shared with one another—almost as if this time I wasn’t in their presence—about the vanity of the Naga Sadhus while preparing for the procession—how the naked wise men whipped up the crowd, infiltrating the limited air with a frenzy.

I listened to the recounting of the line of “floats” with the gurus sitting regally atop their elaborate thrones, surrounded by devotees, tossing marigold flowers to their adoring followers. They told me of a very terrifying moment when they had to cross in front of the line of tightly packed vehicles pulling the gurus, and how it was a do-or-die moment. One false step, one hesitation and any one of them would have sustained major injury.

And then it happened. As the group was trying to get back to our tent village—taking shortcuts, getting lost, ducking under and over fences—they stumbled upon a bridge completely populated by a line of 200,000 Naga Sadhus walking slowly, having just experienced their most holy of baths.

They waved at the few who were there to witness this truly incredible vision. What an utter endowment to stumble upon this unplanned vision, this moment in time that had been unscheduled and that few were able to share. Profound emotions cascaded out of them all.

Sandy grew quiet, and tears shone as she put into words the calm and peace that surrounded the sadhus. “I can’t describe it, Alison. I can’t even process it myself,” Sandy added introspectively.

We all retreated to our tents. I bathed my husband in warm, sudsy, comforting water, and then it was celebration time. We met in Molly’s tent—all of us tired and giddy—with proper libations. It didn’t take much for the alcohol to take hold of my tired wanderers.

It was on our big, comfortable, private bus back to Varanasi that more stories were shared with photos on laptops and cell phones. Our group was soon disassembling. We would share one night in Varanasi—one of the oldest living cities in the world where my husband’s infatuation with Kumbh Mela began.

Three more countries awaited Ken and me … more adventures, photographs and memories. My biggest challenge was how to write the unwritable—having been at the Kumbh but not having been fully at the Kumbh.

Guess what? Ken is making plans to go back.

Whole-Body Wellness

The medical team at The Health & Wellness Center @ BCO helps patients find the path to their best life.