Five Young Competitors Share What it Takes to Make the Jump From Promising to Prolific

The right stuff.

- CategoryPeople

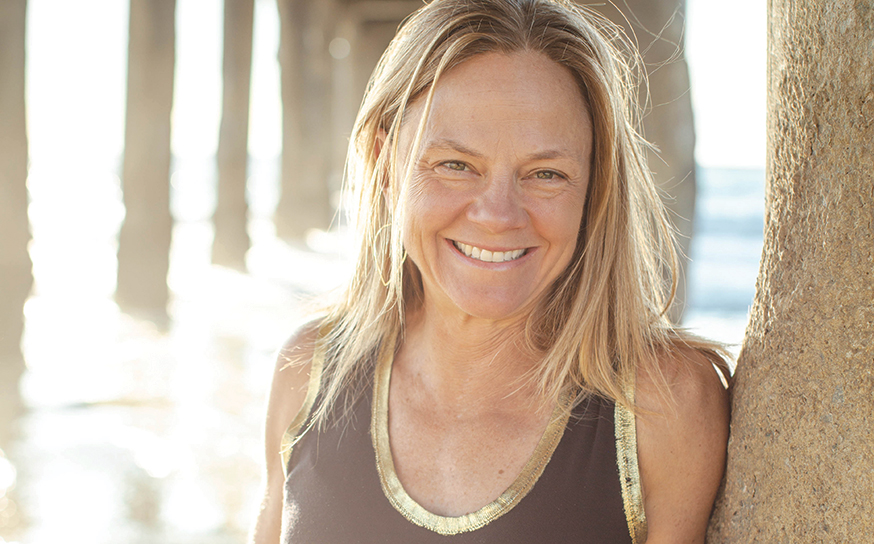

- Written & photographed byKat Monk

The Mehra family is sitting in their Palos Verdes kitchen, jokingly reminiscing about how one of their own became a successful professional runner. A badminton champion in India long ago, Grandma trumps everyone and insists she is the reason.

Rebecca Mehra will be vying for a spot at the Olympic track and field trials in the 800m (½-mile) and 1500m (1-mile) events. The trials will be held in Eugene, Oregon, just a month before the Olympics in Tokyo, Japan.

Rebecca started running at age 11—her first competition a middle school track meet at Peninsula High School. Hooked on running, she soon joined a local running club. But it wasn’t until high school that she really started to take the sport seriously.

“She came to Palos Verdes High School with some running experience, but nobody expected her to perform as well as she did so early on,” explains Brian Shapiro, PVHS athletic director. “Rebecca had a precocious and feisty presence, but underneath she really valued the mentorship and help she got from her teammates and fellow competitors.” As a senior, she won PVHS’s first state championship alongside her freshman sister.

After a trip to Stanford early in her high school days, she knew the university was her dream. Yet she stayed humble, worked hard, trained even harder and took every AP class she could to achieve her goal of admission.

Although Rebecca struggled at Stanford with various stress fractures, she graduated as a three-time All-American, 2017 USA Track & Field Championships semi- finalist in the 1500m and four-time All-Pac-12 in the 1500m. If that is not enough, she also has one of the fastest 1500m times in Stanford University history with 4:11.97.

She has been running professionally for the last two years for Oiselle, a women’s apparel company, after getting both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Stanford. Coming full circle, her professional coach is Lauren Fleshman—her original running idol.

In her first year running the event as a professional, she placed seventh at the USA National Championships in the 800m. She ran a personal best of 4:08.14 in the 1500m and 2:02.55 in the 800m. She recently finished third at the 5th Avenue Mile in New York City against some of the best “milers” in the U.S. and the world with a time of 4:22.0.

“Rebecca is barely getting her feet wet as a pro runner at this level. She has a deep belief in her abilities but doesn’t float away from reality,” adds Lauren. “I like to say she keeps both feet on the ground—but lightly. This is a great way to be open to improvement without the trappings of bad decision-making that come from an unrealistic view of oneself.”

If pole-vaulting talent is genetic, Tate Curran is blessed with some excellent DNA. Tate has numerous relatives who were either pole-vaulters, surfers or both. His Uncle Tim won the pole-vaulting title in 1973, and his father, Anthony, was a two-time state champion in 1977 and 1978.

Tate got hooked on pole-vaulting by age 7 but only vaulted occasionally until he started at Redondo Union High School. Homeschooled most of his life, he continued with independent study in high school so he could pole-vault and also compete on the surf team, his preferred cross-training.

Tate’s best friend’s dad offered his son $100 to beat his record, which inspired Tate to ask his own dad to do the same. With a similar competitive spirit to his son’s, Anthony blurted out, “I will give you $1,000 if you can beat my freshman record.”

In 1978 Anthony set what was then a national high school record when he cleared 14’9” for Encino’s Crespi High. Eventually Tate accomplished the goal and won the bet. “He said he would never bet me again,” smiles Tate.

Tate describes his trajectory as a bit of a Cinderella story. Anthony, the UCLA pole-vaulting assistant coach since 1983, was not able to coach his son due to conflicting schedules. Tate’s dream to go to UCLA and vault for his dad seemed out of the question.

The acceptance rate at UCLA is one of the lowest in the country at 14%. So after graduating high school, he attended El Camino for a year. “I ended up jumping high enough where I could get a scholarship into UCLA, and I instantly became one of the best pole-vaulters in the country,” says the athlete.

While competing in Albuquerque for UCLA, Tate jumped a lifetime best of 17 feet, 6½ inches. “I knew the second I got on the runway that it was going to be a good day,” he says. “My dad coached me right through it.” Adds Anthony, “One of the greatest feelings a dad can have is seeing your son break your record.”

Before he was even old enough to play soccer or T-ball, 4-year-old Jack St. Ivany played in hockey matches for the Lil’ Kings league in El Segundo. Initially part of the swarm chasing the puck down the rink, Jack realized at an early age to strategize and defend the goal too.

“It was an advanced way to look at the game at such a young age,” explains Patricia St. Ivany, Jack’s mom. At that moment, his parents knew he had a future in hockey.

Although many National Hockey League (NHL) players currently live in the South Bay, few were born and raised here. Jack drafted in the fourth round of the NHL to the Philadelphia Flyers. With commitment, dedication and athletic ability, he has achieved success as a defenseman.

The NHL allows their draftees to choose between two options: play 68 to 70 games per season in the professional Western Hockey League (WHL) in Canada or play 30 to 34 games per season for their college team. Players who choose to play in the WHL are no longer eligible for NCAA college play in the United States.

Jack chose to play for his college and is currently a sophomore at Yale University in Connecticut, where he continues to get stronger and develop as a player. In addition to understanding the importance of his education, he also realized that playing too many games in the WHL before a player has fully developed can lead to career-ending injury.

“Jack is someone who can play in all situations, can contribute offensively as well as defend against the other team’s best players,” explains Keith Allain, Yale’s hockey head coach. “He is a player who can log lots of ice time. He had a huge impact last year as a freshman, and with his competitive drive I expect him to improve each and every day.”

While Jack was growing up, he would watch the International Ice Hockey Federation’s World Junior Hockey Championships. “In the world of hockey, it is ‘the’ tournament,” explains Patricia. “The thought of even being a part of the tournament is unimaginable.”

When Jack’s invitation came to be a member of the team, he quickly accepted. “It is the best opportunity to play against the best players in the world,” he explains. The team won the silver medal for the USA after losing to Finland in the finals. Jack is more determined than ever to continue his development and play for the Flyers in the coming years.

Within the athlete’s village of the Pan American Games in Lima, Peru, sat a dining hall the size of a football field filled with hungry, competitive athletes. As Isabelle (Izzy) Connor and four of her USA rhythmic gymnastics teammates came through the doors, they were met with an uproar of applause.

As they walked by fellow U.S. athletes, they were given high fives. Why? They had just won the U.S. a silver medal. Never in Izzy’s life had she felt this level of camaraderie or pride.

Being a gymnast these days is not without challenges. The conviction of Larry Nassar, the former physician at Michigan State University, sent shockwaves through the community. Unlike other countries with full support and stipends, USA Gymnastics lost its sponsorships and is currently trying to rebuild its program. Many gymnasts now have to pay for a significant portion of their pursuit to represent the USA in Tokyo in 2020.

While attending Pennekamp Elementary School, Manhattan Beach Middle School and Mira Costa High School, Izzy trained at the L.A. School of Gymnastics 25 to 30 hours a week. Starting with individual artistic gymnastics, she switched to rhythmic when she was 10 years old. “I preferred the artistry, complexity, beauty and flexibility of rhythmic gymnastics over artistic gymnastics,” she shares.

Rhythmic is a sport that consists of five gymnasts who combine elements of ballet, gymnastics and dance performed on the floor, using apparatus such as a rope, hoop, ball, club or ribbon. Izzy loves connecting with the music so much that she quit gymnastics for a short stint while she pursued dance.

In 2017 Izzy was honored to make the United States Olympic rhythmic gymnastics team, also known as the National Team. She trains at North Shore Rhythmic Gymnastics Center in Chicago four to seven hours a day every day but Saturday. The team has traveled the world competing in countries including Belarus, Russia, Spain, France, Portugal and Italy. Azerbaijan is the next competition that will ultimately decide the team’s Olympic fate for 2020.

With the sun setting in the background, bodies were flipping and flying in the air just above the seas somewhere in the middle of the Caribbean. Mesmerized, 8-year-old gymnast Jacob Haim was watching in awe as a dozen professional divers jumped from 40-foot platforms and trampolines into pools. He was so riveted, he decided diving would be his future.

Jacob soon started taking diving lessons with Coach Hongping Li through the Trojan Dive Club at the University of Southern California. Within two months, the coach put Jacob on his Junior Olympic team. In a local meet just a few months later, Jacob won his first medals in two events: gold and silver. Later that year he also competed in the USA swimming and diving national championships and placed 16th in the United States.

Jacob’s favorite event is the 3-meter dive. “There are more opportunities,” he says. “It’s a board you can take all the way to the Olympics, and it’s much more exciting with lots of hang time.”

In 2014 Jacob won Nationals, one of his proudest moments thus far. His favorite dive on the 3m is a 5335d, a reverse 1½ with 2½ twists. “I have always loved twisters, so I learned a few that I like to do,” he explains.

“He has a long and extended body line, which makes his dives smooth and beautiful to watch in the air,” notes Coach Li. “Jacob knows how to rip into the water; that is very impressive for diving.” Jacob, now 18 and a senior, is diving for Mira Costa High School. The 2024 Olympics could be his ye

Southbay ‘s Annual Spring Style Guide Has the Latest Fashion Trends, Jewelry, Home Goods and Gifts!

Shop local and support our amazing businesses.