Willa Bruce Set Forged a Path That Led to a Successful and Bustling “Resort by the Seaside”

Staring at the sun.

- CategoryPeople

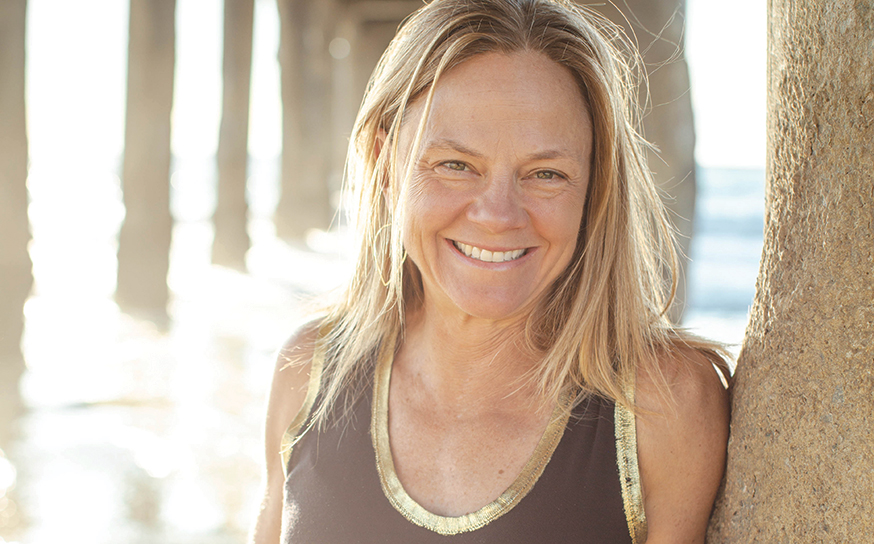

- Written byKat Monk

- Illustrated byNikki Smith

Los Angeles at the turn of the century saw a burgeoning Black population that was vibrant and highly motivated. The city attracted a particularly driven and entrepreneurial group of Black people, according to Alison Rose Jefferson, author of Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era. Embarking on a journey to the Far West was not cheap and required both guts and resources to succeed.

While Charles took a job as a chef on the Union Pacific train between L.A. and Salt Lake City, Willa set her sights on property close to the ocean. She negotiated with real estate agent Henry Willard to buy a beachfront property owned by George H. Peck Jr. between 26th Street and 27th Street for $1,225.

The rural community where the property was located would soon be known as Manhattan Beach. Willa’s choice to negotiate a property deal with a White man during this period of history highlights her bold character. Moreover, the opportunity for a Black person to purchase beachfront property was extremely rare.

Before basic infrastructure arrived at the Beach Cities, the area remained mostly undiscovered to the majority of Los Angeles residents. To spend a day at the beach was a fairly time-consuming and inconvenient process. “It was customary for folks to take a train, streetcar or horse and wagon, fully dressed while they headed to the beach,” says Alison.

Before basic infrastructure arrived at the Beach Cities, the area remained mostly undiscovered to the majority of Los Angeles residents. To spend a day at the beach was a fairly time-consuming and inconvenient process. “It was customary for folks to take a train, streetcar or horse and wagon, fully dressed while they headed to the beach,” says Alison.

Once they arrived, visitors needed a place to change into their bathing suits. Bathhouses soon opened for this purpose, but Black people were not allowed to enter due to legalized segregation.

“Initially she [Willa] started with a pop-up tent and sold water on her property,” explains Alison. “She was feeling out the business because this was at a time when water was being trucked into Manhattan Beach. She had a bigger plan and was methodical about how she was thinking of her business evolving.”

Soon Willa designed a resort where her guests would not only have a place to rent and change into bathing suits but also the ability to enjoy the beach and sea. Swimming pools were not common until the ’20s, so the opportunity to enjoy the beach was welcomed by many.

An article in the Los Angeles Times dated June 24, 1912, shared this description: “The new summer resort which at present consists of a small portable cottage with a stand in front where soda pop and lunches are sold and two dressing tents with shower baths and a supply of 50 bathing suits.”

According to Allison, racism forced Black women to start entrepreneurial businesses because they couldn’t find employment elsewhere. Willa’s vision of opening a resort at the sea for people of her race soon materialized.

She ran an advertisement in local newspaper The Liberator on June 17, 1912, announcing, “the Bruce beachfront” would be a “grand affair,” offering access to the beach and fishing for customers. Selling sodas and renting bathing suits would soon transform into a booming business for the Bruce family.

Willa eventually purchased a second beachfront property for $10. She continued to add services to the resort, expanding to three buildings that included a dance hall, a café and lodging. Live music would echo from the resort as patrons enjoyed hosted parties for a variety of occasions. The California Eagle, owned by a friend of Willa’s, ran advertisements about local church parties to be held at Bruce’s resort.

But the more successful Willa and her resort became, the more harassment she endured—especially during the early 1920s when there were rising local sentiments of a “negro invasion.” Willa was quoted in the Times saying, “Wherever we have tried to buy land for a beach resort we have been refused, but I own this land and I am going to keep it.”

Peck, a wealthy developer and one of the founders of Manhattan Beach, owned the waterfront property in front of Willa’s land over a half-mile from Peck’s Pier to 24th Street. He attempted to deter Willa from running her resort as she desired by forbidding her patrons ocean access through his land. He posted “no trespassing” signs and brought in a constable to arrest Black people who attempted to cross his property.

Though determined to keep her resort in operation, she finally met a threat she could not win. In 1927 the city of Manhattan Beach forced her to close the business, and the property was seized in an eminent domain proceeding. The city stated they needed the property to build a park, which it did decades later.

Willa left Manhattan Beach soon after at the age of 65. She passed away in 1934. As the South Bay continues to confront hard truths of a troubling past, Willa Bruce should be remembered as a trailblazing Black female entrepreneur of her time—forging her way against all odds.

Southbay ‘s Annual Spring Style Guide Has the Latest Fashion Trends, Jewelry, Home Goods and Gifts!

Shop local and support our amazing businesses.